Virginia Hall America’s Unlikely Hero Spy During WWII

Virginia Hall defies stereotypes from the very first moment. Known as the “Limping Lady,” she turns a hunting‑accident amputation into the beginning of a remarkable career in espionage.

With a wooden prosthetic leg she nicknames “Cuthbert,” she slips under the radar and emerges as one of the most daring Allied operatives of World War II.

Her work with both the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) puts her deep behind enemy lines, where she organizes resistance networks, escapes the Gestapo, and ultimately helps liberate parts of occupied France.

Despite her physical limitation and the gender barriers of her time, Hall writes her own rules. The German secret police call her “the most dangerous Allied spy.” Her story blends nerve, grit, and quiet tenacity, reminding us that heroes don’t always look like what we expect.

Origins & Early Life of Virginia Hall

Virginia Virginia Hammel Hall is born on April 6, 1906 in Baltimore, Maryland, into a well‑to‑do family.

She attends boarding school in Baltimore and then studies at Radcliffe College and Barnard College, gaining fluency in French, German and Italian—skills she later uses in wartime espionage.

In 1932 (or 1933 in some sources) a hunting accident in Turkey leaves her with a wounded leg that must be partially amputated; she adapts to life with a prosthetic leg she affectionately names “Cuthbert.”

Her ambition to join the U.S. Foreign Service stalls prejudice against women and amputees blocks her path. Disappointed but undeterred, she moves to Europe, takes consular posts in Poland and Tallinn, and builds her worldview around languages and diplomacy.

In 1940, with war engulfing Europe, Hall volunteers for France’s ambulance service. When France falls to the Nazis, she relocates to London and volunteers for the British SOE in 1941, determined to put her skills, and prosthetic leg, to work in the fight.

This background of wealth, education, injury, rejection and ambition sets the stage for Hall’s transformation into a clandestine warrior.

Appearance and Personal Traits

Virginia Hall didn’t fit the image of a wartime spy. She was a well-dressed woman with a quiet voice and a slight limp from her wooden leg, which she nicknamed “Cuthbert.”

The leg slowed her down but never stopped her. In fact, it became part of her legend. Even the Gestapo, unaware of her true identity, circulated wanted posters describing “the limping lady” as one of the most dangerous Allied agents in France.

She dressed carefully to match her cover identity, often posing as an older woman selling soap or a farmhand. To make disguises more convincing, she sometimes dyed her hair grey or wore bulky clothing to hide her frame. Her limp helped add believability to her character, especially when she passed as a harmless villager.

Beyond appearance, what truly defined Hall was her resilience and calm under pressure. She spoke several languages fluently. French, German, and Italian which helped her blend in while working behind enemy lines.

People who knew her described her as disciplined, clever, and fiercely independent. She carried coded messages, coordinated sabotage missions, and trained French resistance fighters. All while being hunted by Nazi agents.

Her ability to stay invisible in plain sight turned her prosthetic from a liability into a weapon of legend. Though appearance matters less in historical writing, Hall’s physical presence became part of her myth—and her strength.

Major Accomplishments and Achievements

Virginia Hall made her mark as one of the most effective and elusive Allied spies of World War II. Her accomplishments span two major intelligence agencies: Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) and America’s Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the CIA.

In August 1941, the SOE drops her into Vichy-controlled France. Operating under the alias Brigitte LeContre, she builds an underground network known as “Heckler” in the city of Lyon. This group smuggles messages, trains resistance fighters, and rescues downed Allied airmen.

Despite constant risk, Hall works without backup or proper supplies. The Gestapo is aware of her and gives her the title “the most dangerous of all Allied spies.”

When Germany takes over all of France in 1942, Hall’s position becomes too risky. She makes a dramatic escape climbing over the Pyrenees mountains into Spain, on foot, with her prosthetic leg. She travels alone and in winter. British records note that she mentions her wooden leg in radio messages, jokingly saying she hopes “Cuthbert” doesn’t give her trouble.

In 1944, Hall returns to France, this time with the OSS. Disguised as a farm worker, she operates under the codename “Diane.” She organizes parachute drops, trains French Maquis fighters, blows up bridges, cuts telephone lines, and helps delay German reinforcements before D-Day.

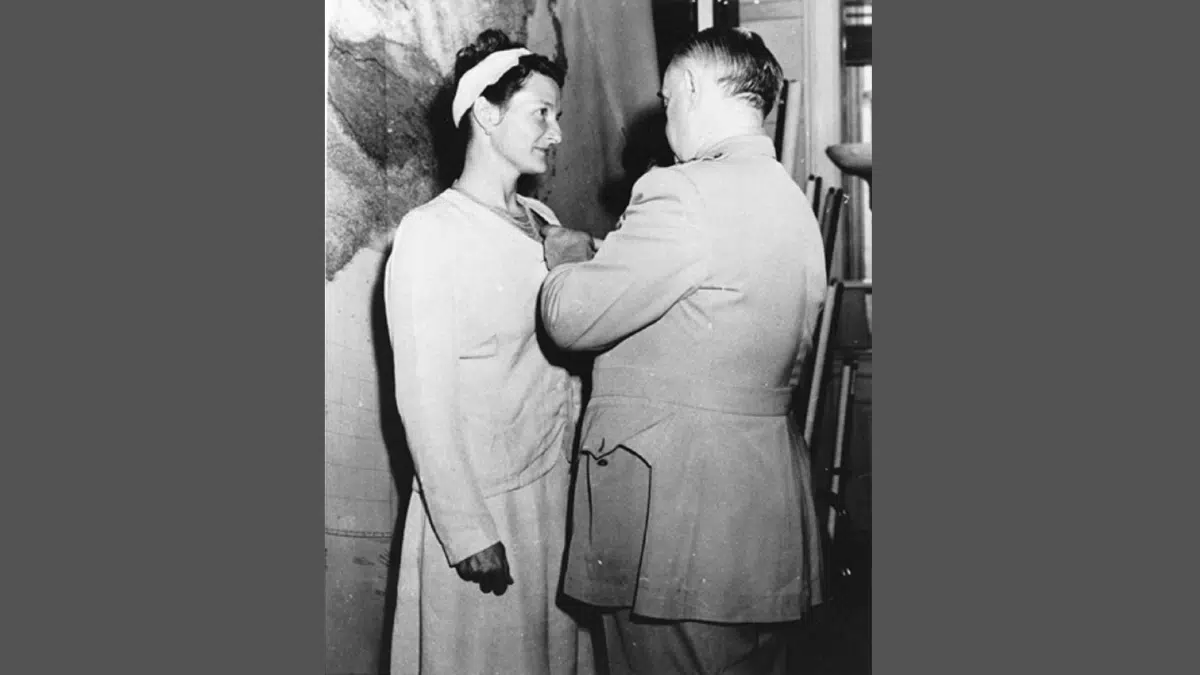

Her efforts earn her the Distinguished Service Cross, making her the only civilian woman in WWII to receive that U.S. honour. She also receives France’s Croix de Guerre and is named a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).

After the war, she joins the CIA, though her role is limited due to discrimination against women. Still, her legacy grows, and her wartime efforts remain unmatched among Allied spies.

How Virginia Hall Died

After the war, Virginia Hall returns to the United States and continues working in intelligence. She joins the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 1951 and serves there for over a decade, mostly in the Special Activities Division. Despite her wartime success, she often faces sexism and is kept from leadership roles. Still, she remains committed to the work, helping train new agents and advising on European operations.

In 1966, Hall retires quietly to a farmhouse in Barnesville, Maryland, with her husband, Paul Goillot—himself a former OSS agent she worked with during the war. She rarely speaks publicly about her wartime experience, keeping much of her story out of the spotlight for decades.

On July 8, 1982, Virginia Hall dies in Rockville, Maryland at age 76. She is buried in Druid Ridge Cemetery in Pikesville, Maryland, not far from where she was born.

Her contributions receive wider attention after her death. The CIA later names a training facility after her, and new books and films help bring her story to a broader audience. Today, she stands as a symbol of resilience, determination, and unmatched bravery.

Legacy and Recognition of Virginia Hall

Virginia Hall’s work stays secret for much of her life. The nature of her missions which were dangerous and classified keeps her out of the spotlight, even after the war ends. For decades, few outside the intelligence community know how much she contributes to the Allied victory in Europe.

That begins to change in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The CIA names a training facility after her and includes her in its official history, calling her one of the most valuable agents of World War II. In 2006, she is included in the U.S. Army Military Intelligence Hall of Fame. The Virginia Hall Expeditionary Center now bears her name at CIA Headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

Her story spreads further through books, documentaries, and films. The 2019 movie A Call to Spy introduces her to a wider audience, portraying her work with the SOE and OSS. Authors like Sonia Purnell (A Woman of No Importance) help cement Hall’s place in the public imagination.

Today, Hall is viewed as a pioneer. Not just for her espionage work, but for overcoming both gender bias and physical disability in a field dominated by men. Her courage, resourcefulness, and refusal to quit make her a role model for women in intelligence and the military.

Though she avoids fame in her lifetime, Virginia Hall now stands recognized as one of the most effective and unlikely heroes of the Second World War.

Learn more about other women in warfare:

- Violette Szabo: World War II Spy and British Heroine

- Eastern Asia Women of Warfare: Warriors Who Shaped History

- India Women of Warfare: Heroines, Warriors and Leaders

- Brave Women Disguised As Men Join Their Nation’s Military

Interesting Facts About Virginia Hall

1. She Named Her Wooden Leg “Cuthbert”

Virginia Hall lost her lower left leg in a hunting accident in Turkey, but she didn’t let it stop her. She used a prosthetic leg, which she nicknamed “Cuthbert”. During a dangerous escape over the Pyrenees mountains, she radioed to London, joking that she hoped “Cuthbert” wouldn’t cause problems. The SOE replied they weren’t familiar with any agent named Cuthbert—missing the joke entirely.

2. The Nazis Considered Her Extremely Dangerous

The Gestapo called her “the most dangerous Allied spy” and placed her at the top of their most-wanted list in France. Posters described her as “the limping lady” but never caught her. She changed identities, wore disguises, and even filed her prosthetic leg to make walking easier in rough terrain.

3. She Ran Entire Spy Networks—Alone

In Vichy France, she managed one of the most successful resistance networks, called “Heckler,” before any Allied armies even landed. She arranged supply drops, sabotage missions, and rescue efforts for downed airmen—all without direct support.

4. She Worked for Three Major Intelligence Services

Hall worked with French intelligence, Britain’s SOE, and later America’s OSS and CIA. Very few individuals operated at her level across three allied nations.

Conclusion

Virginia Hall’s life shows what true courage looks like. She faced rejection, injury, and constant danger, yet chose to fight anyway. With a wooden leg, fluent language skills, and unmatched determination, she became one of the most effective spies of World War II.

Her work with the SOE, OSS, and later the CIA helped shape the Allied resistance in France. She trained fighters, organized missions, and outsmarted the Gestapo—all while remaining calm, strategic, and deeply committed.

Today, her name appears on CIA buildings and bookshelves, but for years, her story remained in the shadows. Now, Virginia Hall stands as a powerful reminder that grit, intelligence, and quiet strength can outmatch even the fiercest enemies. She didn’t just fight the Nazis. She redefined what heroism could look like.